But… The Emperor Has No Clothes!

March 3, 2009 Leave a comment

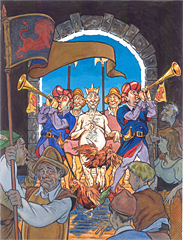

Remember the Hans Christian Anderson story, The Emperor’s New Clothes? A couple of swindlers take advantage of a vain emperor by promising to fashion a beautiful new suit. The suit, however, was a nonexistent scam that was invisible to all, including the emperor himself. No one had the courage to speak up and tell him the suit was invisible, so he paraded around naked until finally a child pointed out what was obvious to all.

Remember the Hans Christian Anderson story, The Emperor’s New Clothes? A couple of swindlers take advantage of a vain emperor by promising to fashion a beautiful new suit. The suit, however, was a nonexistent scam that was invisible to all, including the emperor himself. No one had the courage to speak up and tell him the suit was invisible, so he paraded around naked until finally a child pointed out what was obvious to all.

How often does this same scenario replay itself in the world of corporate business? Companies that stifle open and honest feedback (either unwittingly or by design) encourage just this sort of enabling behavior. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon. For any number of reasons, certain projects, initiatives, and decisions are considered political hot potatoes. It might be due to a significant investment of time or capital, or simply because the initiative is the pet project of a politically powerful executive. The justifications for wanting to hear only what they want to hear are both numerous and convincingly valid. Convincing, that is, to the emperor who doesn’t want to be told that his “new suit” is transparent. But by creating an environment in which feedback is reduced to self-serving affirmation, executives isolate themselves in their own fictional sphere of reality.

Companies (and people) have a bad habit of using the cost of an investment (be it a program, idea, or initiative) as justification for its ongoing implementation. In reality, however, any unrecoverable cost is sunk once invested. Regardless of whether the project is a success or failure, there’s no getting the investment back. Therefore, the justification for the ongoing implementation of an initiative should be based solely on the viability and merits of the initiative itself, independent of the unrecoverable investment. Otherwise, it’s like eating spoiled food (or wearing an invisible suit) just because you paid for it. Similarly, any company initiative that is flawed should either be immediately fixed or killed, regardless of how much it originally cost. You simply cannot justify the continued implementation of a flawed program based on its original cost. And if speaking up to acknowledge or challenge the flaws is tantamount to career suicide, whose interest is being served?

Regardless of the reasons or circumstances, when a company allows its culture of communication and feedback to become constipated, so much so that acknowledging flaws in an initiative or decision is perceived as potentially career damaging, they do themselves a dangerous disservice. No one will tell the emperor he is naked if he fears for his job or his standing in the company.

Perhaps even worse than a flawed initiative going unchallenged is the resulting sense of apathy that such closed-mindedness breeds. Lower level management and staff eventually stop caring whether the emperor is naked or not. And why shouldn’t they? If the emperor only wants to hear how beautiful his suit appears, and any discussion of the fact that it’s actually invisible risks a figurative beheading, then why speak out? Why take the risk? Why care?

I was speaking with several members of our management team the other day about the staff and a particular area in which they need to improve. In the course of the conversation one of my management trainees jokingly made the comment, “They’re afraid of you, Bryant.” I didn’t think too much about it at the time, but in the days since I keep coming back to what she said. I have a pretty healthy relationship with every individual on my team – they are all responsive to direction and also readily come to me with concerns and problems. I know with a reasonably high degree of certainty that I am viewed as fair and equitable. Further, I think most of them feel comfortable enough to challenge me on issues when there is strong disagreement or if I happen to personally offend them in some way.

I was speaking with several members of our management team the other day about the staff and a particular area in which they need to improve. In the course of the conversation one of my management trainees jokingly made the comment, “They’re afraid of you, Bryant.” I didn’t think too much about it at the time, but in the days since I keep coming back to what she said. I have a pretty healthy relationship with every individual on my team – they are all responsive to direction and also readily come to me with concerns and problems. I know with a reasonably high degree of certainty that I am viewed as fair and equitable. Further, I think most of them feel comfortable enough to challenge me on issues when there is strong disagreement or if I happen to personally offend them in some way. Developing a culture of alignment in any organization or team requires a considerable investment in time, but it’s not rocket science. You have to realize, however, that any attempt to alter the culture must be carefully planned and executed. Managers too often function as information conduits. They orchestrate and delegate, hopefully participate, but when new directives are introduced, they simply call a meeting and make an announcement. If opposition is anticipated, they might host a breakfast or lunch meeting. For some reason, food is generally assumed to be a mitigating distraction for unpalatable announcements. And yet, while I can’t argue the benefits of a doughnut induced stupor early in the morning, the effects will be short lived unless the general health and culture of the team can readily weather a little upheaval.

Developing a culture of alignment in any organization or team requires a considerable investment in time, but it’s not rocket science. You have to realize, however, that any attempt to alter the culture must be carefully planned and executed. Managers too often function as information conduits. They orchestrate and delegate, hopefully participate, but when new directives are introduced, they simply call a meeting and make an announcement. If opposition is anticipated, they might host a breakfast or lunch meeting. For some reason, food is generally assumed to be a mitigating distraction for unpalatable announcements. And yet, while I can’t argue the benefits of a doughnut induced stupor early in the morning, the effects will be short lived unless the general health and culture of the team can readily weather a little upheaval.

Recent Comments